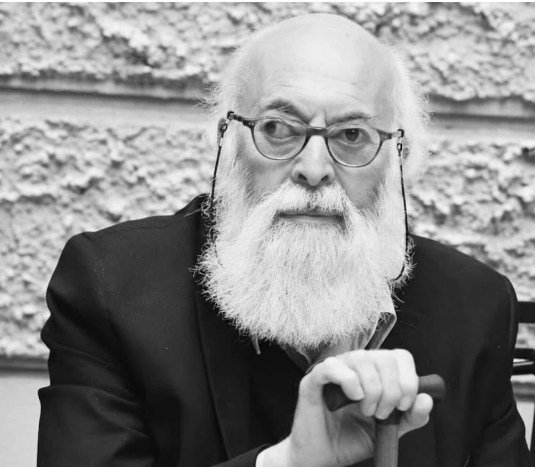

He was 18 years old. His weapon was a bottle of acid. And he saved 14,000 lives.

Paris, 1943. Adolfo Kaminsky was an apprentice dyer working in a textile shop when the Nazis occupied France. He learned chemistry through fabric, understanding how certain acids interact with certain inks, which solvents dissolve which pigments, how to manipulate color at the molecular level.

He had no idea this knowledge would become the difference between life and death for thousands.

When the Gestapo began systematically identifying, documenting, and deporting French Jews to concentration camps, their primary tool was bureaucracy. Identity papers. Ration cards. Travel permits. Every document stamped, sealed, certified. And on Jewish identification papers, one word appeared in bold ink: “JUIF.”

That single word was a death sentence.

The French Resistance found Kaminsky and brought him a challenge: could he remove that stamp without destroying the document? Most forgers couldn’t do it. The inks were designed to be permanent. Any attempt to erase them would damage the paper, making the forgery obvious.

Kaminsky stared at the document under lamplight. Then he remembered something from the dye shop. Lactic acid. It could dissolve the specific blue ink the French government used without destroying the paper fibers beneath.

It worked.

But erasing the word was only the beginning. He had to forge replacement information. New names. New birthdates. New identities. Each document had to be perfect because a single mistake, one inconsistency, one slightly wrong shade of ink, meant torture and death not just for the person carrying the paper, but for everyone who helped them.

The Resistance set him up in a hidden attic laboratory on the Left Bank. The orders came constantly. Fifty birth certificates for children being smuggled to Switzerland. Two hundred ration cards for families hiding in attics and cellars. Three hundred transit passes for an escape route through Spain.

Kaminsky worked under a single weak lightbulb. Chemical fumes from bleach and acids burned his throat and stung his eyes until tears ran down his face. His fingers became permanently stained with ink. The tiny room grew thick with the smell of solvents.

And then he did the math.

He calculated that each document took approximately two minutes to forge properly. That meant in one hour, he could create thirty documents. Thirty chances at survival. He developed a brutal equation that haunted him: every hour he slept, thirty people could die. Every minute he rested was a minute someone remained trapped, vulnerable, waiting.

“If I sleep for an hour, 30 people will die,” he told his fellow Resistance workers.

So he stopped sleeping.

During one horrific week, word came that an orphanage sheltering 300 Jewish children was about to be raided. The children needed papers immediately or they would be loaded onto trains to Auschwitz. Kaminsky locked himself in the attic and worked for two days and two nights without stopping. He forged birth certificates until his vision blurred and doubled. He forged until his hand cramped into a rigid claw and he had to massage it back to function. He forged until exhaustion finally overpowered him and he collapsed face-down onto the worktable.

He woke an hour later in a panic, furious at himself. Thirty people. He had potentially killed thirty people by sleeping.

He didn’t eat. He went directly back to work.

The children escaped.

Month after month, year after year, Kaminsky worked in that dim attic. The Nazis grew more sophisticated in their document security. He grew more sophisticated in his forgery techniques. It became a silent war fought with chemistry and precision, where victory was measured in lives that continued, in children who grew up, in families that survived.

By the time Allied forces liberated Paris in August 1944, Adolfo Kaminsky had created forged papers that saved an estimated 14,000 men, women, and children from the gas chambers.

He never accepted a single cent for his work. When people offered payment, he refused. The idea of charging money to save a life was, to him, morally incomprehensible.

After the war, Kaminsky became a photographer. He lived quietly, modestly, invisibly. He never spoke about what he had done. Not to neighbors. Not to colleagues. For decades, not even to his own children. The hero who had saved thousands simply melted back into ordinary life.

Only near the end of his life did he finally share his story, and when he did, the world learned something it should never forget: that courage doesn’t always carry a gun, that heroism doesn’t always wear a uniform, and that one person armed with knowledge, conviction, and stubborn refusal to sleep can stand against an empire of evil and win.

Adolfo Kaminsky died in 2023 at age 97. But the 14,000 lives he saved have become families, communities, generations. His legacy isn’t measured in monuments or medals.

It’s measured in people who exist because a teenager with a bottle of acid decided sleep was less important than their lives.